Achebe says: “The first to object were the Northerners led by the Sardauna, who were followed closely by the Awolowo clique that had created the Action Group. Achebe says: “The first to object were the Northerners led by the Sardauna, who were followed closely by the Awolowo clique that had created the Action Group......Read The Full Article>>.....Read The Full Article>>

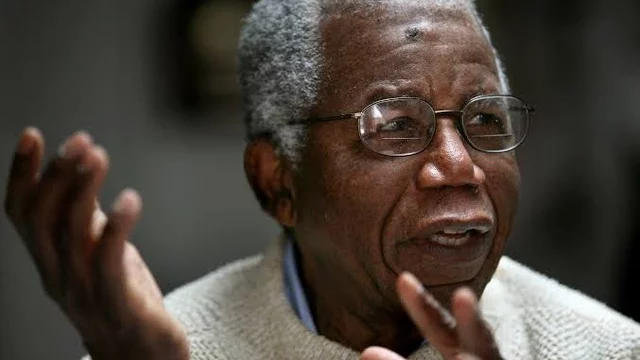

Foremost novelist, Chinua Achebe, has laid the blame for the deep-seated disunity confronting Nigeria on the doorsteps of Northern and Yoruba leaders who he said opposed the idea of one Nigeria before and after independence.

In his new book, which has become largely controversial in the past days, Mr. Achebe said while Igbo leaders and intellectuals worked hard, promoting the idea of one Nigeria, Northern leaders, led by the Sardauna of Sokoto, Ahmadu Bello, and their Yoruba counterparts, led by Obafemi Awolowo, worked in the opposite direction, making sure the dream of a united Nigeria did not materialize.

Mr Achebe made the claim on Page 51 of the 333-page book, saying, “The original ideal of one Nigeria was pressed by the leaders and intellectuals from the Eastern Region. With all their shortcomings, they had this idea to build the country as one.

“The first to object were the Northerners led by the Sardauna, who were followed closely by the Awolowo clique that had created the Action Group.

“The Northern Peoples Congress of the Sardaunians was supposed to be a national party, yet it refused to change its name from Northern to Nigerian Peoples Congress, even for the sake of appearances. It refused right up to the end of the civilian regime.”

The author did not give any details regarding how and where the Northern and Yoruba leaders opposed the idea of a united Nigeria.

In the book, Mr. Achebe was full of praises for Nigeria’s first President, Nnamdi Azikiwe, who he described as the father of African independence.

“The father of African independence was Nnamdi Azikiwe,” Mr. Achebe said on page 41 of his book. “There is no question at all about that. Azikiwe, fondly referred to by his admirers as “Zik,” was the preeminent political figure of my youth and a man who was endowed with the political pan-Africanist vision. He had help, no doubt, from several eminent sons and daughters of the son.”

Mr. Achebe criticism of Mr. Awolowo’s civil war policies in the book had earlier sparked a fierce disagreement between the Yoruba and the Igbo in Nigeria and fired up a rare dichotomy between the two ethnic nationalities , with each side teaming with their kinsman.

Nearly a week after an excerpt of Mr. Achebe’s memoir, blaming Mr. Awolowo for starving to death over two million Biafran children, became public, leading Yoruba leaders and activists have poured invectives on the writer.

In turn, Mr. Achebe’s Igbo kinsmen have sided with him, justifying his claims and attacking Yoruba critics in return.

But our reporter, who skimmed through the book last night, says Mr. Achebe in one instance eulogized Mr. Awolowo in the book, portraying him as a master political tactician, a committed leader of his people, a unifying factor, an excellent organizer and an erudite and accomplished lawyer.

Mr. Awolowo was clearly one of Nigeria’s dominant political figures of his time, Mr. Achebe wrote in the book.

On Page 45 of the book, Mr Achebe wrote of Mr. Awolowo: “By the time I became a young adult, Obafemi Awolowo had emerged as one of Nigeria’s dominant political figures. He was an erudite and accomplished lawyer who had been educated at the University of London. When he returned to the Nigerian political scene from London, Awolowo found the once powerful political establishment of western Nigeria in disarray – sidetracked by partisan and intra-ethnic squabbles. Chief Awolowo and close associates reunited his ancient Yoruba people with powerful glue –resuscitated ethnic pride-and created a political party, the Action Group, in 1951, from an amalgamation of the Egbe Omo Oduduwa, the Nigerian Produce Traders’ Association, and a few other factions.

“Over the years Awolowo had become increasingly concerned about what he saw as the domination of the NCNC by the Igbo elite, led by Azikiwe. Some cynics believe the formation of the Action Group was not influenced by tribal loyalties but a purely tactical political move to regai regional and southern political power and influence from the dominant NCNC.

“Initially Chief Obafemi struggled to woo support from the Ibadan-based (and other non-Ijebu) Yoruba leaders who considered him a radical and a bit of an upstart. However, despite some initial difficulty, Awolowo transformed the Action Group into a formidable, highly disciplined political machine that often outperformed the NCNC in regional elections. It did so by meticulously galvanizing political support in Yoruba land and among the riverine and minority groups in the Niger Delta who shared a similar dread of the prospects of Igbo political domination.”

Below are other mentions of Mr. Awolowo in the book.

Achebe’s latest work: There was a country

Page 51: “The original ideal of one Nigeria was pressed by the leaders and intellectuals from the Eastern Region. With all their shortcomings, they had this idea to build the country as one. The first to object were the Northerners led by the Sardauna, who were followed closely by the Awolowo clique that had created the Action Group. The Northern Peoples Congress of the Sardaunians was supposed to be a national party, yet it refused to change its name from Northern to Nigerian Peoples Congress, even for the sake of appearances. It refused right up to the end of the civilian regime.”

Page 86: “By March 1967, two months after the summit in Aburi, Ghana, the Aburi Accord resolutions had yet to be implemented, and there was growing weariness in the East that Gowon had no intention of doing so. The government of the Eastern Region warned Gowon that his repeated failure to act on issues pertaining to Nigerian sovereignty could lead to secession Gowon responded by issuing a decree, Decree 8, which called for the resurrection of the proposals for constitutional reform promulgated during the Aburi conference.

But for reasons hard to explain other than as egotistical self-preservation, members of the federal civil service galvanized themselves in energetic opposition to the agreements of the aburi Accord. Seeing this development as a strategic political opening, the Yoruba leader, Obafemi Awolowo, the West’s political opening, heretofore nursing political trouble himself, including prior imprisonment for sedition, insisted that the federal government remove all Northern military troops garrisoned in Lagos, Ibadan, Abeokuta and throughout the Western Region – a demand similar to those Ojukwu had made earlier, during the crisis.

Awolowo warned Gowon’s federal government that if the Eastern Region left the Federation, the Westen Region would not be far behind. This statement was considered sufficiently threatening by Gowon and the federal government to merit a complete troop withdrawal.”

Page 88: “The first part of May 1967 saw the visit of the National Reconciliation Commission (NRC) to Enugu, the capital of the Eastern Region. It was led by Chief Awolowo and billed as a last-minute effort at peace and as an attempt to encourage Ojukwu and Eastern leaders to attend peace talks at a venue suitable to the Easterners. Despite providing a friendly reception, many Igbo leaders referred to the visit disdainfully as the chop, chop, talk, talk, commission”.

Page 227: “A day later, on January 15, 1970, the Biafran delegation, which was led by Major General Phillip Effiong and included Sir Louis Mbanefo, M.T. Mbu, Colonel David Ogunewe, and other Biafran military officers formally surrendered at Dodan Barracks to the troops of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. Among the Nigerian delegation were: General Yakubu Gowon; the deputy chairman of the Supreme Military Council, Obafemi Awolowo; leaders of the various branches of the armed forces, including Brigadier Hassan Katsina, chief of staff; H.E.A. Ejueyitchie, the secretary to the federal military government; Anthony Enahoro, the commissioner for information; Taslim Elias, the attorney general; and the twelve military governors of the federation.”

Page 233: “It is important to point out that most Nigerians were against the war and abhorred the senseless violence that ensued. The wartime cabinet ofGeneral Gowon, the military ruler, it should also be remembered, was full of intellectuals like Chief Obafemi Awolowo among others who came up with a boatload of infamous and regrettable policies. A statement credited to Awolowo and echoed by his cohorts is the most callous and unfortunate: all is fair in war, and starvation is one of the weapons of war. I don’t see why we should feed our enemies fat in order for them to fight harder.

“It is my impression that Awolowo was driven by an overriding ambition for power, for himself and for his Yoruba people. There is, on the surface at least, nothing wrong with those aspirations. However, Awolowo saw the dominant Igbos at the time as the obstacles to that goal, and when the opportunity arose – the Nigeria-Biafra war – his ambition drove him into a frenzy to go to every length to achieve his dreams. In the Biafran case it meant hatching up a diabolical policy to reduce the numbers of his enemies significantly through starvation — eliminating over two million people, mainly members of future generations.”

Page 234: “If Gowon was the “Nigerian Abraham Lincoln,” as Lord Wilson would have us believe, why did he not put a stop to such an evil policy, or at least temper it, particularly when there was international outcry? Setting aside for the moment the fact that Gowon as head of state bears the final responsibility of his subordinates, and that Awolowo has been much maligned by many an intellectual for this unfortunate policy and his statements, why, I wonder, would other “thinkers,” such as Ayida and Enahoro, not question such a policy but advance it?